What is Community Solar?

Community Solar projects create shareable, renewable energy

Do you want to power your home using renewable energy, but can’t install rooftop solar? Perhaps you have a shaded roof, live in a condo, or are not a property owner, but want your electricity fossil-fuel free. In many locations, there is a great solution – community solar, or “rooftop solar, without the rooftops.”

Community solar – also called a community solar project, solar garden, or shared renewable energy plant – describes solar energy used by multiple households sourced by a shared solar plant. Community solar projects exist in half of US states, so it may be in your area. If not, just keep an eye out – according to the Solar Energy Industries Association (SEIA), the community solar market should continue to boom; more community solar was installed in one-quarter of 2016 than the entire year of 2015.

There are multiple structures of community solar agreements that this article will review. If you’re lucky, there will be a variety of options for you to choose from, but you also may be constrained to whatever exists in your area. Either way, this will be important to help your understanding of using community solar, so read on!

The benefits of community solar

Before we dive into the types of solar, let’s review the benefits. The first is financial – while solar on your rooftop might drastically reduce, or even eliminate your electric bill, you’ll still be paying for community solar. However, you will still be paying less than you would typically pay your utility company for the same amount of energy. Most community solar is set up with finance as the primary driving force.

The second is environmental – the energy you purchase from a community solar source is carbon-free, ensuring that your electricity consumption doesn’t contribute to greenhouse gas emissions. There are some community solar projects set up primarily for this outcome.

The following categories of community solar are outlined by the American Council on Renewable Energy (ACORE), the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL), and the Solar Electric Power Association (SEPA). These organizations categorize community solar in slightly different manners.

It is important to note that there are no official, standardized categories under any policy or law (14 different states and D.C. have their own community solar laws), but the following structures encompass most community solar options.

1. Utility-led model

Under a utility-led or utility-sponsored model, the utility company owns the solar plant and households purchase the electricity directly from them. According to SEPA, utility-led community solar programs accounted for approximately 60% of active US programs as of 2016.

The benefits to the customer show up on their electricity bill, where they will see a credit for their share of the plant’s power production. Some utilities can pass on the benefits of federal or state tax incentives to customers to offset costs. The electricity produced by the solar garden will go to the utility’s grid, where it merges with other electricity.

Some utilities are investing in community solar to hedge against the threats that home rooftop solar pose to their business model (selling fossil fuel-generated electricity to homes). This way, the utility can take advantage of homeowners’ desire to go solar while still being involved in the model. No matter the motivation, this is a great opportunity to utilize renewable electricity.

This is different than a ‘Green Power’ arrangement, in which you can opt-in to asking your utility to source your electricity from renewable sources. Those arrangements typically manifest simply in higher electric rates on your bill.

SEPA further breaks down utility-sponsored or utility-led programs into two subcategories (pg 15) – Pilot Programs and 2nd Generation Programs.

Example – Sacramento Municipal Utility District

Sacremento Municipal Utility District, or SMUD, drives a variety of community solar projects in locations like schools, community centers, and larger farms to benefit many households. One model that SMUD uses is SolarShares, a subscription service for households within its utility coverage area that costs a flat monthly fee and provides credits for the energy that a ‘SolarShare’ creates.

SMUD uses a ‘blended rate’ approach in its solar projects to account for scaling future development – when a home signs up, they are offered a price based on the current solar available, but the rate has the potential to change in the future if more projects are built that lower prices.

2. Utility-led model – Pilot Programs

Pilot Programs are typically smaller-scale programs initiated by a utility working their way into the community solar market, or a small utility or cooperative. They provide the utility with the benefit of appealing to customers seeking green energy and testing out the mechanisms of community solar.

These projects are typically under 500kW, and some utilities will contract out services to third parties that they do not have the size or capability to support. These are differentiated from larger 2nd-gen Programs in that they typically only serve a small number of people.

Example – Ellensburg, Washington

One example of a utility-led pilot program model was created by the municipal utility in Ellensburg, Washington in 2006 – at the time, it was the first community solar project in the US. The program is only 110kW and generates electricity for about 30 households, who are credited for electricity produced from their portion of the solar garden.

3. Utility-led model – 2nd gen programs

Second-generation programs typically follow a smaller-scale pilot program model, when the utility decides to expand the community solar potential to the rest of their customers. These larger programs can drastically dwarf the pilots, going as high as 20MW. The programs may vary in how customers are rewarded (or provide households multiple options).

It is important to distinguish a utility-led program from the next category, a third-party program. The utility company will likely contract with an outside party to construct and maintain a large-scale community solar project, but because the program is led by the utility as a part of their larger market, it is still utility-led.

Example – Orlando Utilities Commission

One utility with a matured program is the Orlando Utilities Commission (OUC). The key feature of their community solar program is a 400 kW array created in 2012 (built as covered parking).

They market the community solar to their customers as a great substitute for rooftop solar if that isn’t feasible – “the amount of energy produced by your solar blocks will appear on your monthly bill just as if you had rooftop solar panels.” Households pay $0.13/kWh for the electricity.

4. Special-purpose entity (SPE) or third-party model

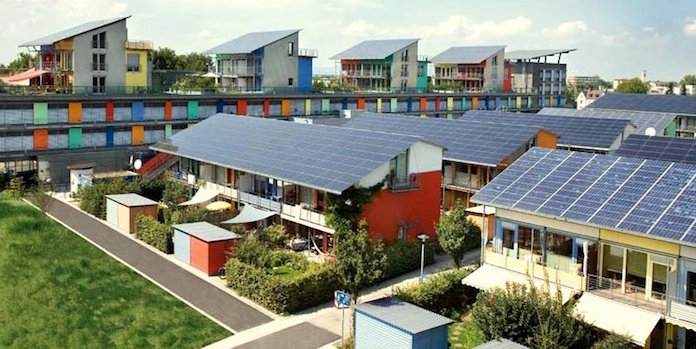

A Solar Settlement

This model allows for community members to buy into community solar via ownership or subscription (more on the differences in these structures below). An ‘entity’ owns the property the solar infrastructure is on – this entity (or SPE) being either a corporation, limited liability company, cooperative, or partnership.

They then manage the distribution, billing, and customers. SPEs typically set up these models in a way that allows them to pass tax incentives for solar down to the individual households after they claim them at their level. Like we mentioned when describing the utility-led programs, there are some blurred lines between these models at times.

The third-party-led model can be best distinguished by its status as a ‘for-profit program’, and that it is led by a company that generally manufactures, installs, and runs these programs as a primary mechanism of their business model. Some of the companies leading this model include Recurrent Energy and Sunshare.

The models tend to be large (over 1 MW), with multiple prices or mechanisms, in order to appeal to a wide variety of customers and maximize profit opportunity for the company.

Example – Clean Energy Collective

Clean Energy Collective constructs for-profit community solar gardens in 12 states, and its primary community solar product is called RooflessSolar. They seek customers directly and market the program (and thus it is third-party-led) even though the electricity still moves through the utility’s grid.

To date, they have 100 projects online and serve more than 3,000 people. The billing is coordinated by the company using their own software, called RemoteMeter. Several examples of Clean Energy Collective’s projects include a large-scale deployment of solar in Colorado, and a 1.1 MW project being constructed in Massachusetts.

5. SPE / Third-party model – ownership structure

This is a subset of the third-party or SPE model, distinguished by its structure as it relates to the homeowners investing.

One way of buying into a community solar program is through actual ownership – you own a certain number of solar panels in an array, and the power produced by your portion is all for you. This is typically set up by purchasing solar panels through the project developer (either upfront or via a loan, similar to rooftop solar purchases), who will then install them.

Participants are typically only able to purchase the amount needed to fund their electricity bill, so if your home has a load of 4kW, that is how much capacity should be purchased.

Example – Holy Cross Energy, Colorado

The Holy Cross Energy project was administered through Clean Energy Collective as a small-scale 78 kW array (its first project). Customers were given the opportunity to purchase one of the panels in the array upfront for $725 in exchange for credits on their energy bill for the power produced by the panel(s) they owned. The deal lasts for 50 years, providing benefits to households long after their initial purchase.

6. SPE / Third-party model – subscription structure

Farmer Brubaker sells his excess power to the community

Another way of buying into community solar is through a subscription program, where you just agree to purchase your electricity from a solar farm, but do not actually own any panels. This does not require any upfront purchasing and is generally administered by the third party that owns the solar farm.

Example – Minnesota Community Solar

Residents in Minnesota that are in the Xcel Energy utility territory are able to subscribe to Minnesota Community Solar (MNCS), instead of owning portions of their community solar arrays.

Households get a credit on their electricity bill each month for the electricity generated by their portion of the garden (with some money set aside for MNCS maintenance and monitoring). This is a structure available at no upfront cost as long as households maintain a high credit score.

7. Nonprofit model

The Truckee Meadows Community College whose solar was installed by a non-profit

This model utilizes donors to create a community shared solar installation, generally owned by a non-profit. The non-profit – commonly a school, a church, or another community center – can either use the solar it produces to offset its own utility bills, and/or set up the system for net metering.

Depending on the state and locality the shared solar system is in, money can go back to the donors (individual households) through a group billing process, or through VNM, providing credits on donors’ electric bills. This type of model has seen some success in providing energy to low-income communities.

Example – Grand Valley Power, Colorado

In 2015, Grand Valley Power developed a community solar garden for low-income households in partnership with a non-profit called GRID Alternatives. GRID was able to construct the 24 kW solar garden using donations and contributions of time and materials and provide the power with no upfront fees and a low rate to low-income subscribers.

After four-year cycles, households that no longer classify as low-income are removed and their places are given to other homes in need.

The future of community solar

These models will continue to evolve as community solar – a relatively new business model – continues to mature and companies determine the most profitable and effective ways to design programs.

Utility Dive notes that programs in the future could be mostly utility-owned, privately owned, or a mixture of both; may incorporate energy storage or other types of renewable energy or may utilize different payment methods (owning the solar panels vs. being credited for using renewable electricity).

Hopefully, this article helped clear up any uncertainties about community solar – industry leaders believe that one of the largest hurdles for this type of renewable energy is a lack of understanding about the opportunities. This market will continue to grow, so be sure to keep an eye on community solar programs in your area!

Image Credits under CC License via Flickr – 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8